Blog

All the latest info and insights from the Akka team

Featured

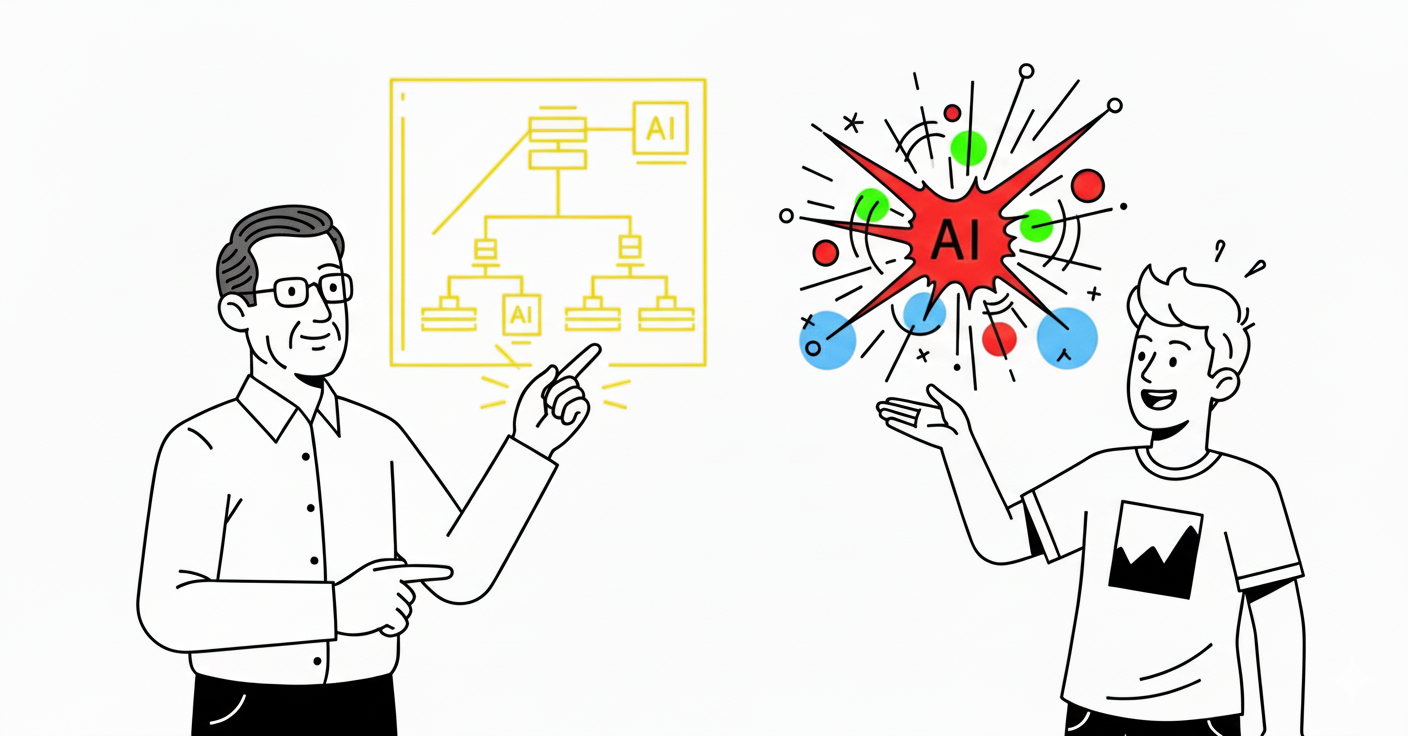

What is Agentic AI?

What is Agentic AI? Watch this video to understand what it is, and the risks of operating a distributed system that infuses non-deterministic LLMs.

Agentic AI: Why Experience Matters More Than Hype

Experience matters more than hype. Why most agentic projects fail—and what 15 years of production-hardened experience reveals about building them right.

News: Akka and Deloitte Canada Collaborate to Deliver Agentic AI at Scale

Akka and Deloitte join forces to solve critical enterprise agentic AI issues, including cost, performance, and resilience.